Post by : Priya

Photo:Reuters

In mid‑2025, the G7—the group of seven major advanced economies—announced a bold commitment: to mobilize one trillion US dollars by 2030 to help poorer countries tackle climate change. This pledge signals a potential milestone in global climate diplomacy—but the challenge lies in turning promise into practice.

1. Why $1 Trillion Matters

Developing nations face mounting threats: rising seas, worsening storms, prolonged droughts, and shrinking harvests. These countries need vast resources to adapt and transition to cleaner energy. Independent economic studies estimate that emerging markets and developing countries—outside China—will require roughly $1 trillion per year by 2025, rising to $2–2.4 trillion annually by 2030 for climate action and sustainable investment

Historically, developed nations promised $100 billion annually by 2020. That goal was finally reached in 2022, according to OECD data, with $115.9 billion reported in 2022

. But this figure, while symbolic, falls far short of the true scale needed.

What Did the G7 Actually Pledge?

At their 2025 summit, G7 leaders affirmed they will play a major role in mobilizing climate finance toward a collective $1 trillion goal by 2030. The funds would come from a mixture of public grants, development bank lending, and private investments

Global Solutions Initiative

World Resources Institute

. This reflects a long‑standing call for a “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG) under the Paris Agreement framework

However, the pledge currently lacks specific details: how much each country will contribute, in which years funds will be delivered, and how much will come as grants versus loans. Climate advocacy groups stress that transparency and firm timelines are crucial if the commitment is to be meaningful.

Where the Money Could Come From

Climate finance can take several forms:

Public grants and concessional loans, often administered through multilateral climate funds like the Green Climate Fund or Adaptation Fund

Private investment mobilized by public support, such as guarantees or blended finance vehicles that reduce risk and attract capital

National policy tools, including carbon pricing, fossil‑fuel levy revenues, or solidarity taxes—like proposed surcharges on aviation or cryptocurrency transactions—that could channel funds to vulnerable countries

What Experts and Advocacy Groups Say

Climate policy analysts welcome the G7’s willingness to step up, but emphasize that the real test lies in execution. As one expert noted, “Trust is the real issue here… stepping up and leading encourages others to follow”

Groups such as Oxfam argue that at least half of any new climate finance should be directed toward adaptation and "loss and damage" support—areas that are chronically underfunded

Others warn that relying too heavily on loans, instead of grants, may deepen debt burdens in vulnerable countries—especially when public grants represent just a portion of total climate flows (often 69% loans)

How This Compares to COP29 Outcomes

At COP29 in late 2024, countries agreed to a new NCQG framework: developed countries should lead in mobilizing $300 billion per year by 2035, within a broader goal of $1.3 trillion annually by 2035

Yet, developing nations rejected the smaller $300 billion figure as insufficient, calling out the long runway and lack of urgency

The Wall Street Journal

By comparison, the G7 pledge is more ambitious in scale and timing—targeting $1 trillion by 2030 rather than 2035. Nevertheless, critics stress that pledges without accountability and clear structure risk repeating past failures.

Key Challenges Ahead

Funding gaps remain vast. Studies suggest that even with $1 trillion committed, global financing needs by 2030 may be closer to $1.3–1.5 trillion annually

Private finance alone isn’t enough. Many climate adaptation and resilience efforts—such as coastal protection, flood defenses, or emergency planning—are unattractive to investors seeking profit. These require public and grant support

Accountability is key. Without clear reporting frameworks, countries may count ineligible expenses or double count investments. Independent monitoring and robust definitions are vital to build trust

Emissions reductions lag intention. Beyond finance, the G7 must reduce its own emissions more aggressively. Current policies suggest G7 nations may cut emissions by only 19–33% by 2030—far below the 58% or more needed to stay within the 1.5 °C Paris goal

From Words to Action

For the G7’s pledge to have real impact, several steps are essential:

Kazakhstan Boosts Oil Supply as US Winter Storm Disrupts Production

Oil prices inch down as Kazakhstan's oilfield ramps up production, countered by severe disruptions f

Return of Officer's Remains in Gaza May Open Rafah Crossing

Israel confirms Ran Gvili's remains identification, paving the way for the Rafah border crossing's p

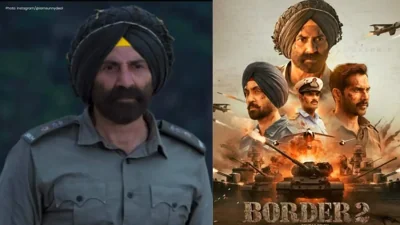

Border 2 Achieves ₹250 Crore Globally in Just 4 Days: Sunny Deol Shines

Sunny Deol's Border 2 crosses ₹250 crore in 4 days, marking a significant breakthrough in global box

Delay in Jana Nayagan Release as Madras HC Bars Censorship Clearance

The Madras High Court halts the approval of Jana Nayagan's censor certificate, postponing its releas

Tragedy Strikes as MV Trisha Kerstin 3 Accident Leaves 316 Rescued

The MV Trisha Kerstin 3 met an unfortunate fate near Jolo, with 316 passengers rescued. The governme

Aryna Sabalenka Advances to Semi-Finals, Targeting Another Grand Slam Title

Top seed Aryna Sabalenka triumphed over Jovic and now faces Gauff or Svitolina in the semi-finals as