Post by : Anees Nasser

China has once again placed its mark on the map of lunar aspirations, reaffirming its target of landing humans on the Moon by the year 2030. The goal, announced by the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) during a press briefing alongside the naming of a new astronaut crew, underscores the country’s commitment to establishing itself as a leading power in deep‑space exploration. This mission is not simply a scientific endeavour; it is a symbol of national ambition, technical maturity and strategic positioning in an increasingly competitive space environment. As China moves steadily toward this objective, the implications for the global space race are profound.

At the heart of this push is a sequence of technological developments: the next‑generation carrier rocket Long March 10, the crew module Mengzhou, the lunar lander Lanyue (literally translated “Embrace the Moon”), a specially designed lunar extravehicular suit (Wangyu) and a crewed lunar rover (Tansuo). According to official statements, many of these systems are reaching key test milestones.

The CMSA has publicly stated that “all stages of the human landing programme development are progressing steadily” and reiterated that the goal “to achieve a human landing on the Moon by 2030 remains firm.” In the same announcement, China revealed the next astronaut trio — Zhang Lu, Wu Fei and Zhang Hongzhang — who will join the orbiting station programme aboard Tiangong and serve as the next generation taikonauts preparing the way for lunar missions.

Moreover, China outlined a rigorous testing schedule ahead: integrated tests of the lander, thermal and dynamic pressure tests for the spacecraft, launch site infrastructure upgrades and orbital‑ and lunar‑transfer validation flights.

There are several motives behind China’s accelerated lunar push. First, the Moon offers a platform for scientific research — from lunar geology and volatile detection to long‑duration human habitation studies — that supports China’s broader space ambitions. Second, the lunar programme serves as a tool of national prestige, demonstrating China’s technological and organisational capability on the world stage. Third, strategic considerations are key: as other powers revive lunar ambitions (like the Artemis programme led by NASA), China’s Moon‑goal cements its role as a principal actor in the next era of space exploration.

Timing is critical. A 2030 target places China in direct competition with the U.S. and other nations planning crewed lunar returns. Achieving a landing by that date would mark the first human return to the Moon in decades, and the first ever by China or any other country beyond the U.S.

China’s lunar programme is organised in multiple interconnected phases of increasing complexity. The earlier robotic missions (such as Chang’e 5 and Chang’e 6) demonstrated sample‑return capability and deepened China’s experience in lunar operations.

Now the focus shifts to human lunar landing: the Long March 10 rocket is designed to launch crewed lunar missions; the Mengzhou spacecraft will carry astronauts; the Lanyue lander will conduct the surface mission; specialized lunar suits and a rover will allow exploration and mobility on the Moon. Infrastructure on Earth — launch complexes, tracking stations, ground networks — is being scaled accordingly.

Recent tests include the second‑stage propulsion static fire, lander touchdown and take‑off simulation, zero‑altitude escape tests for the crew module. These are crucial to validate full system readiness.

China’s announcement has immediate ripple effects for other space‑faring nations. The U.S., which retains historic dominance in crewed lunar landings, faces renewed pressure. For example, the Artemis programme’s timeline has encountered delays and criticism of its contractor arrangements.

China’s Moon‑goal also invites new international cooperation or competition. Partnerships between China and Russia for lunar bases have been speculated; while Western nations may seek to deepen alliances to counterbalance China’s momentum. The lunar surface is once again a frontier of both science and geopolitics.

If China lands its astronauts on the Moon by or before 2030, it would become the second nation in history to do so — a milestone with profound strategic, symbolic and economic value.

Despite the momentum, China’s task is far from easy. Landing humans on the Moon requires perfect integration of rockets, spacecraft, landers, suits, life support and mission operations — all within an unforgiving environment. Testing, validation, redundancy and safety remain high stakes. The timeline is tight: achieving crewed lunar landing in less than five years demands flawless execution.

Logistics and infrastructure remain massive undertakings. China must ensure launch readiness, supply lines, crew training, medical and radiation mitigation, lunar surface shelters and rover operations. On top of this, mission‑architecture decisions still await finalisation: landing site (likely near lunar south pole), mission duration, surface mobility, rendezvous and return strategies.

Strategically, international collaboration or isolation will shape outcomes. If China moves forward with a moon base or joint missions, other nations may feel compelled to respond with greater investment. On the flip side, any major setback or accident will carry reputational risk at home and abroad.

China’s lunar agenda also offers potential spin‑offs in technology, industry and education. Large rocket manufacturing, crewed systems, lunar mobility, robotics and space infrastructure all fuel domestic capability and may feed a global space economy. As China invests in lunar programmes, private‑sector partners, suppliers and satellites may benefit.

This sets up a dynamic field: companies and nations seeking lunar surface services, moon‑rover technologies, habitats, power systems, in‑situ resource utilisation will see growing demand. The Moon may become a proving ground for future lunar tourism, mining of lunar ice and rare‑earths, and deeper solar‑system missions.

China’s commitment may accelerate global competition, spurring cost‑reduction, innovation and new business models in space exploration. The ’race’ may no longer be purely national but integrated with commercial players and multi‑national enterprises.

For regions like Asia and the Middle East, China’s lunar ambitions present opportunities and caution. On one hand, they may offer cooperation — payloads for lunar missions, scientific instruments, or partnerships in future lunar infrastructure. On the other hand, geopolitical alignments could shift: space capability is increasingly tied to economic, diplomatic and security influence.

Countries in the Middle East are investing in space and looking to establish their own presence. A Chinese‑led lunar initiative may open pathways for collaboration or competition in areas like lunar communications, satellite services, and crew training. Emerging economies may find a partner role in lunar supply chains or payload contributions. The broader future of space governance, law, resource extraction and lunar property rights also begins to matter for all regions.

In the immediate future (next 1‑2 years), watchers should look for:

Launch of additional test flights of Long March 10 and Mengzhou spacecraft

Integrated lander descent/launch rehearsals for Lanyue

Selection of lunar landing site (likely near south‑pole region)

Formal announcement of international cooperation frameworks or payload invitations

More astronaut rotations on Tiangong space station to build long‑duration experience

Milestones in lunar rover, extravehicular suit and lunar surface mobility demonstration

Each of these steps will signal whether China remains on track for its 2030 goal or whether schedule delays creep in.

China’s settlement of a 2030 human Moon‑landing goal marks a powerful declaration: the space frontier is shifting, and new players are rising. If realised, China will join an elite club of space‑faring nations and reshape the architecture of lunar exploration, cooperation and competition. For global science, industry and diplomacy, the stakes are high.

The Moon is not just a destination; it is the beginning of a new era of human presence off Earth. As China accelerates its lunar programme, the world must watch, adapt and engage — because the space race is no longer dormant, and the Moon is set to become a theatre of 21st‑century partnership, rivalry and discovery.

This article is intended for informational purposes only and is based on publicly available statements and reporting. It does not represent any official position of China, NASA or other agencies. Readers are encouraged to consult original sources and updates from relevant space agencies for the latest developments.

Kazakhstan Boosts Oil Supply as US Winter Storm Disrupts Production

Oil prices inch down as Kazakhstan's oilfield ramps up production, countered by severe disruptions f

Return of Officer's Remains in Gaza May Open Rafah Crossing

Israel confirms Ran Gvili's remains identification, paving the way for the Rafah border crossing's p

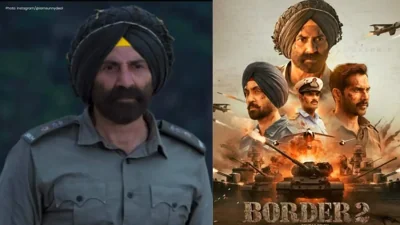

Border 2 Achieves ₹250 Crore Globally in Just 4 Days: Sunny Deol Shines

Sunny Deol's Border 2 crosses ₹250 crore in 4 days, marking a significant breakthrough in global box

Delay in Jana Nayagan Release as Madras HC Bars Censorship Clearance

The Madras High Court halts the approval of Jana Nayagan's censor certificate, postponing its releas

Tragedy Strikes as MV Trisha Kerstin 3 Accident Leaves 316 Rescued

The MV Trisha Kerstin 3 met an unfortunate fate near Jolo, with 316 passengers rescued. The governme

Aryna Sabalenka Advances to Semi-Finals, Targeting Another Grand Slam Title

Top seed Aryna Sabalenka triumphed over Jovic and now faces Gauff or Svitolina in the semi-finals as