Post by : Priya

Photo:Reuters

The Brahmaputra River is not just a body of water. It is a lifeline, a cultural symbol, and a point of geopolitical interest. Flowing through Tibet, India, and Bangladesh, the river plays a vital role in the lives of millions. However, a new development on the river’s upper course has drawn international attention: China’s plan to build a massive hydroelectric dam near the border with India.

While initial reports triggered concerns in India over the potential impact on water flow, flood control, and regional security, India’s top hydrological experts and government officials have now clarified that India’s water supply remains secure. The dam may be large, but India's systems are strong—and perhaps stronger than most assume.

Understanding the Brahmaputra: Geography, Culture, and Importance

The Path of the Brahmaputra

Originating from the Angsi Glacier in Tibet, the river is called the Yarlung Tsangpo in China. It travels eastward across the Tibetan Plateau before curving sharply to the south at the Great Bend near Namcha Barwa, where it enters India through Arunachal Pradesh as the Brahmaputra. After coursing through the states of Arunachal Pradesh and Assam, it flows into Bangladesh as the Jamuna River, where it eventually merges with the Ganges and flows into the Bay of Bengal.

This 2,900-kilometer river is unique because it traverses three countries, has varied climatic zones, and supports biodiversity and communities at every turn. In India alone, the Brahmaputra feeds the lives of more than 130 million people, especially in the Northeast region, which heavily relies on it for agriculture, drinking water, and transportation.

China’s Mega Dam: What We Know

The Project Plan

China’s construction of a “mega-dam” on the Yarlung Tsangpo was first mentioned in the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025). The proposed site is in Medog County, located just across the border from Arunachal Pradesh.

Reports suggest that the dam could potentially produce 60 gigawatts of electricity, more than twice that of the Three Gorges Dam, the current largest in the world.

According to Chinese authorities, the dam is part of their broader strategy for renewable energy development and carbon neutrality. China argues that the dam will help achieve its clean energy goals without diverting water.

Why It’s Called a “Run-of-the-River” Dam

Experts describe the project as a “run-of-the-river” dam. This means it does not store large volumes of water but simply channels flowing water through turbines to produce electricity. While this limits its ability to store or divert water, it also means less environmental disruption—at least on paper.

Initial Reactions: Fear and Mistrust in India

History of Mistrust

The relationship between India and China has long been marked by suspicion, especially over border disputes in Arunachal Pradesh and Ladakh. When news about the dam surfaced, many Indian citizens and leaders worried that China might gain leverage by controlling the Brahmaputra’s water flow.

In a region where water security is deeply tied to national security, fears were understandable. Social media trended with hashtags like #SaveBrahmaputra and #WaterWar, and political leaders demanded clarity from Beijing.

India’s Scientific Analysis: Facts over Fear

What India Found

In response to these concerns, India’s Ministry of Jal Shakti, along with the Central Water Commission (CWC), conducted a thorough study based on satellite images, seasonal data, and hydrological models. Here are their key findings:

70% of Brahmaputra's water comes from rainfall within India, not from upstream Tibet.

The Chinese dam, being run-of-the-river, cannot store large volumes of water or suddenly stop the flow.

Any sudden releases from the dam can be monitored in real-time by India’s satellite and river monitoring systems.

China and India exchange hydrological data during flood seasons under a bilateral agreement.

In simple terms: China may control a stretch of the river, but it cannot hold India hostage over water.

The Local View: Voices from Assam and Arunachal Pradesh

Renu Das, a teacher from Dibrugarh, said,

“The river gives us food, water, and joy. But it also brings floods. If China does something wrong, we suffer. We hope the government stays alert.”

Dorjee Tashi, a farmer in Tawang, added,

“We trust our Army and our government. They know how to protect us. The Brahmaputra will never dry up.”

Hydropolitics in the Region: A Delicate Balance

Shared Rivers, Shared Risks

India and China share over 15 rivers, including the Brahmaputra, Sutlej, and Indus tributaries. In international law, rivers crossing national borders are often governed by treaties or water-sharing agreements.

However, China has no formal water-sharing treaty with India—only agreements to share data. This puts India in a diplomatically tricky spot. Unlike Pakistan, which has a clear Indus Waters Treaty with India, India has no binding legal agreement with China on water sharing.

Yet, despite the lack of formal treaty, India has consistently received flood-season water data from China since 2002.

Independent Voices Weigh In

What Global Hydrologists Say

Dr. Michael Kugelman, an expert on South Asia at the Wilson Center, said:

“China’s dam projects are a concern, but India is not helpless. Its water resilience comes from domestic rainfall and internal rivers. The Brahmaputra flows strong within India.”

Professor Nandita Bose, a river management expert at IISc Bangalore, added:

“We must understand the difference between real threats and imagined fears. Diplomacy and science must work together. Panic helps no one.”

India’s Strategic Moves: Strengthening Water Security

In the wake of China’s plans, India has taken several important steps:

Hydrological Monitoring Upgrades

Installation of satellite-based river flow monitoring in Arunachal Pradesh and Assam.

Expansion of the Flood Early Warning System in Northeast India.

Development of a River Basin Authority to coordinate between states.

New Dams and Water Projects

India is now planning its own hydroelectric projects in Arunachal Pradesh to better utilize the river’s flow. These include:

Subansiri Lower Project (2,000 MW)

Dibang Multipurpose Project (2,880 MW)

These efforts serve dual purposes: power generation and water control during floods.

The Role of Diplomacy: Quiet Talks, Not Loud Threats

While public outrage makes headlines, diplomacy happens behind closed doors. India has quietly raised its concerns with China through official channels. Sources say China has reassured India that the dam is for electricity and not water diversion.

Moreover, India has approached international forums like the UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses to press for fair and cooperative river management practices.

Kazakhstan Boosts Oil Supply as US Winter Storm Disrupts Production

Oil prices inch down as Kazakhstan's oilfield ramps up production, countered by severe disruptions f

Return of Officer's Remains in Gaza May Open Rafah Crossing

Israel confirms Ran Gvili's remains identification, paving the way for the Rafah border crossing's p

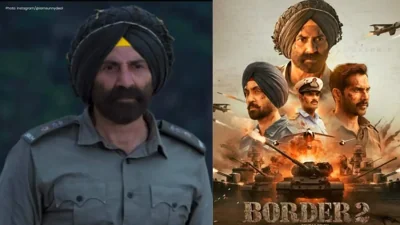

Border 2 Achieves ₹250 Crore Globally in Just 4 Days: Sunny Deol Shines

Sunny Deol's Border 2 crosses ₹250 crore in 4 days, marking a significant breakthrough in global box

Delay in Jana Nayagan Release as Madras HC Bars Censorship Clearance

The Madras High Court halts the approval of Jana Nayagan's censor certificate, postponing its releas

Tragedy Strikes as MV Trisha Kerstin 3 Accident Leaves 316 Rescued

The MV Trisha Kerstin 3 met an unfortunate fate near Jolo, with 316 passengers rescued. The governme

Aryna Sabalenka Advances to Semi-Finals, Targeting Another Grand Slam Title

Top seed Aryna Sabalenka triumphed over Jovic and now faces Gauff or Svitolina in the semi-finals as